Beyond Safer Streets: What the City’s LSDF Means for Cape Town’s Housing Future

Why the City’s new spatial plan could reshape who gets to live in Cape Town’s CBD — and what still needs fixing before it’s real.

Cape Town’s new Local Spatial Development Framework (LSDF) for the CBD goes far beyond mobility. At its core, it’s a blueprint to tackle one of the city’s most pressing challenges: housing affordability. While the draft Mobility Plan has drawn headlines for reshaping streets and transport, it’s the LSDF that lays the foundation for a more inclusive, better-located future — one where the right to live in the city isn't reserved for a privileged few.

More Than Just Movement

The Mobility and Accessibility Plan is just one piece of a much bigger picture. The LSDF sets out a long-range spatial plan for how land in the CBD is used, developed, and protected. It’s the City’s way of shaping what the inner city will look and feel like in 10 to 20 years — not just in terms of how people move, but who gets to live there, and how land, buildings, and public investment can be used to undo spatial exclusion.

At the centre of that: affordable housing.

What the LSDF Actually Does

The LSDF aligns zoning and development priorities with broader public goals — like access, equity, and climate resilience. It identifies public land that can be unlocked for housing. It links urban planning to infrastructure, mobility, and design. And crucially, it creates the policy space for inclusionary housing and land value capture.

It doesn’t pretend to have a quick fix, but it sets out tools and locations to shift the CBD’s housing reality over time.

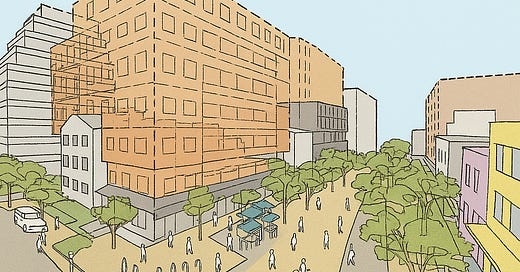

1. Mixed-Use and High-Density Housing Where It Matters

The LSDF promotes denser, mixed-use development on underused and state-owned land — like City-owned sites along Drury Street and around the Civic Centre. These areas are close to jobs, transport, and services, helping reduce the cost of living by cutting down on long, expensive commutes.

2. Inclusionary Housing — A Policy Taking Shape

A key step forward is the introduction of spatially targeted inclusionary housing tools. These could work through overlay zones or by granting developers extra rights (like height or density) in exchange for providing affordable units. While the City’s Inclusionary Housing Policy is still in draft form, the LSDF lays the groundwork to implement it in specific precincts like the East City, Foreshore, and Station areas.

Proposed incentives include fast-tracked approvals, relaxed parking requirements, and planning fee exemptions. These mechanisms don’t just make affordable housing possible — they make it viable.

3. Making Public Land Work for the Public

The plan identifies strategic public land parcels for mixed-income residential use. That includes sites like Bloemhof Street, Robbie Nurock, and the Civic Centre precinct. These projects would ideally be delivered through public-private partnerships that balance financial feasibility with social return.

Side note: we would like to see vacant parking land near Parliament being repurposed for all sorts of housing.

4. Capturing Land Value for Public Benefit

The LSDF proposes a land value capture model — allowing additional floor area if developers contribute to public goods like affordable housing, public realm upgrades, or sustainability features. It’s not just incentives; it’s a trade: more for more.

5. Regulating Short-Term Rentals

The LSDF also surfaces a structural barrier to affordability: over 70% of CBD residential units are currently used for hospitality and short-term rentals. There’s currently no mechanism to regulate this. The document calls for policy reform to address the unchecked growth of Airbnbs and their impact on long-term housing availability.

Cape Town has a housing crisis, and rentals are becoming unaffordable for locals. To balance lower municipal incomes and the rising cost of maintaining the city, the City of Cape Town needs to urgently start charging business rates on homes rented out year-round as short-term lets — in other words, properties no longer serving as residences, but as commercial income-generating assets.

6. A Work in Progress — but With Teeth

This isn’t just a wishlist. Overlay zone reviews are already in motion to embed inclusionary housing requirements into Cape Town’s planning system. And the LSDF itself is backed by an implementation pipeline with specific projects, lead departments, and timelines — many in the 2025–2030 horizon.

What’s Still Missing — and Why It Matters

While the LSDF makes bold commitments to housing affordability, several of its key tools and ideas are still in early or conceptual stages. There’s no doubt it lays out a more inclusive vision for the CBD, but many of the mechanisms — like inclusionary housing overlays or using land value capture — will only become real through future zoning reforms, intergovernmental coordination, and political will.

What’s more, there are practical limitations to what the LSDF can enforce on its own. From unresolved planning conflicts to limited clarity on enforcement, it’s crucial to understand where the plan sets direction — and where it still relies on broader policy shifts, departmental follow-through, or outside institutions to make that direction real.

Here’s what still needs sharper definition or stronger commitment:

Timing and implementation clarity

Inclusionary housing and land value capture tools are still in draft form and rely on future amendments to the Municipal Planning By-law (MPBL).Clearer definition of the City’s role

The LSDF names the City as provider, enabler, and regulator of affordable housing, but stops short of detailing what role it will take on in each precinct.Trade-offs with heritage and height restrictions

Existing overlays and form controls may constrain where dense or affordable development can occur, and the plan doesn’t fully reconcile those tensions.Delivery risks and intergovernmental dependencies

Key public land parcels depend on cooperation with entities like PRASA and Transnet — which the City cannot control directly.No firm enforcement mechanisms

While the plan supports inclusionary zoning and value capture, it lacks concrete tools to monitor delivery or hold developers accountable once rights are granted.Failure to tax short-term rentals like businesses

Cape Town has a housing crisis, and rentals are becoming unaffordable for locals. To balance lower municipal incomes and the growing cost of maintaining the city, the City of Cape Town must urgently begin charging business rates on homes rented out as short-term lets all year round — properties no longer serving as homes, but as commercial income-generating assets.

What It All Adds Up To

The LSDF offers more than spatial guidelines. It’s a declaration that a just, liveable city isn’t possible unless we address who has access to the city itself. It links land use, housing, mobility, and economic policy in one integrated approach — and it starts with the principle that everyone deserves a fair shot at living near opportunity.

Building on Previous Public Comments and Advocacy

This vision didn’t emerge from nowhere. In our previous submissions to the City’s draft Municipal Planning By-law (MPBL) reforms, Young Urbanists and others called for bold changes to planning tools that too often protect exclusion over inclusion. We pushed for:

A formal overlay zone that supports affordable and mixed-income housing in high-access areas like the CBD.

Reduced parking minimums for centrally located affordable developments.

Easier land use processes for social housing institutions and non-profit developers.

Land value capture mechanisms to deliver public benefits as part of private development rights.

Action on short-term rentals to protect long-term housing supply.

Those comments were made in coordination with a growing civic community that sees housing as a right, not a luxury. Now, many of these same ideas are taking root in the LSDF — not as slogans, but as structured proposals, supported by spatial policies, mapped opportunities, and a rollout pipeline.

That’s progress — but only if we keep showing up, speaking up, and pushing it forward.

The deadline to comment is 11 May. Don’t miss your chance to shape this plan.

You can read the plan and submit your input at:

www.capetown.gov.za/HaveYourSay